Lake of Many Colours

Kalamalka Lake Colours

Visit Kalamalka Lake in late summer or early fall and you will witness a remarkable display of seemingly-supernatural colour. If you visit the lake often, you might notice that turquoise hues of the water shift throughout the growing season. This phenomenon is the result of sunlight reflected by tiny white crystals in the water called marl. Marl is formed when the dissolved calcium carbonate in the lake crystalizes. After forming, the marl slowly sinks into the deep water and stops reflecting light. The lake colour we perceive at any moment is a consequence of the amount of marl near the lake surface. Water temperature plays a critical role in this process since marl forms faster in warmer water.

Marl lakes are rare. Kalamalka Lake owes its calcium carbonate to limestone deposited by the receding Fraser Glacier over 10,000 years ago. A complex set of chemical interactions are necessary to trigger marl to form from calcium carbonate present in a lake. In Kalamalka Lake, the process is initiated in mid-summer when photosynthesizing phytoplankton raise the pH of the lake. Water quality improves during a marl event, as crystallization binds nutrients previously suspended in the water into marl. The reduction in the over-abundance of lake nutrients results in a decline in algae.

Steep and Deep

Underwater Topography

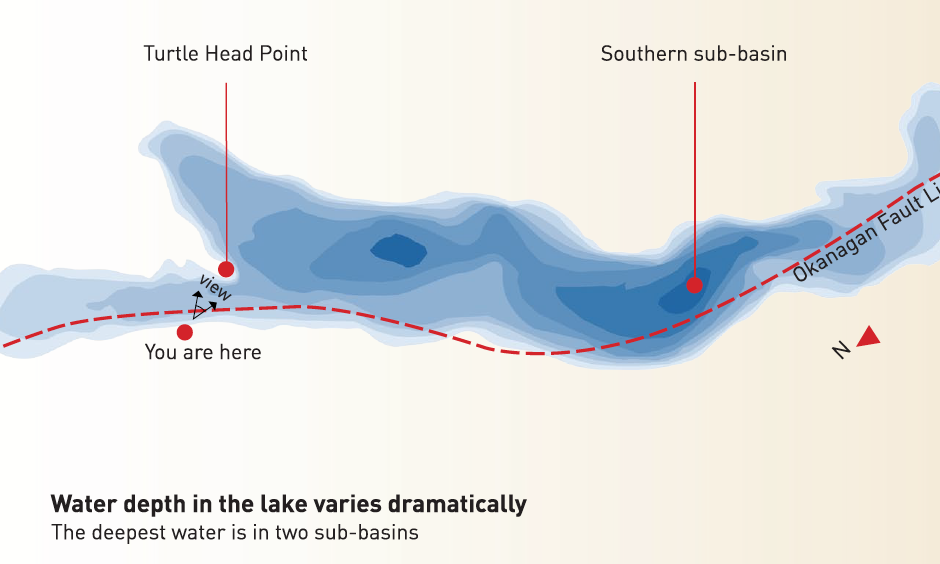

Ask around and most locals will tell you that Kalamalka Lake is deep but what does that actually mean?

Kalamalka Lake sits in a deep U-shaped trench where its water depth varies dramatically. All of the lake’s underwater maximum depths can be found in the southern sub-basin. Here the maximium water depth is 146 metres and the sediment layer on the lake bottom is thickest at 272 metres. This sediment sits on glacier-eroded bedrock which dips 26 metres below sea-level in the southern sub-basin.

Kalamalka Lake is a classic a ‘fjord lake’. The bedrock below Kalamalka Lake was carved by the movement of the Fraser Glacier over 10,000 years ago. It has steep bedrock slopes which visitors can see rising out of the water. The lake’s thick flat layer of sediment came from the silt suspended in the glacial water which settled to the lake bottom.